Introduction

Introduction Introduction

IntroductionWhy all the fuss over a bunch of ground squirrels? The answer lies in the farmer and rancher's view of prairie dogs' impact to their livelihood. Prairie dogs compete with livestock for forage. They clip vegetation to maintain a view of their surroundings and eat the same grasses that would otherwise be available for cattle and horses. Over long periods of prairie dog activity grass species which ranchers find most desirable can disappear. They are often replaced with less palatable grass species with lower nutritional value. In farmed ground prairie dogs can decimate or destroy a crop of alfalfa, grains or hay.

People also compete with prairie dogs for shelter. Expanding urban areas, especially the rapidly growing Front Range in Colorado, has seen the conversion of prairie dog towns into people towns-as housing and commercial development replaces grasslands. No government-sponsored campaign against the prairie dogs has been necessary to insure the dominance of human uses in our towns and cities. Once prairie dogs are removed, the habitat is changed to such a degree prairie dogs usually don't have the opportunity or ability to reestablish themselves.

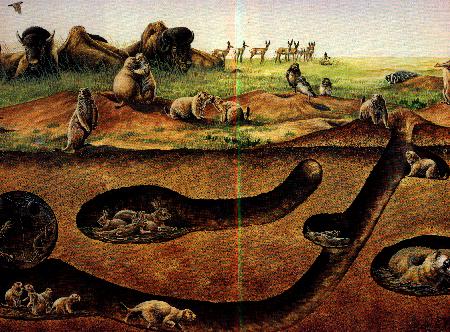

Their

burrow system has been studied well enough so that we know today one might find

the following: (I) a "listening post room" just under the surface

and set offfrom their main burrow, (2) a separate "room" which they

use as a toilet and which may be emptied periodically, (3) a nesting/sleeping

chamber lined with dried grass. The nesting chambers are often elevated from

the bottom of their tunnels so they remain dry when water flows into the burrow

entrance.

Their

burrow system has been studied well enough so that we know today one might find

the following: (I) a "listening post room" just under the surface

and set offfrom their main burrow, (2) a separate "room" which they

use as a toilet and which may be emptied periodically, (3) a nesting/sleeping

chamber lined with dried grass. The nesting chambers are often elevated from

the bottom of their tunnels so they remain dry when water flows into the burrow

entrance.

The social life of black-tailed prairie dogs has been the topic of much study and interest by field naturalists and ecologists. For example, prairie dogs have a vocabulary of about 11 distinct calls and a host of postures and displays. When detecting danger, prairie dogs alert other members of the colony. They make a loud "chirk" while standing, on two or four legs, or lying prostrate in a burrow entrance. This anti- predator call has been given a variety of names including the "squit-tuck", the warning bark, and the "tik-uhl". It is something of an evolutionary puzzle why prairie dogs would risk their own skin by drawing the attention of a predator in order to save other members of their town. Some scientists believe that prairie dogs only mean to warn their close kin.

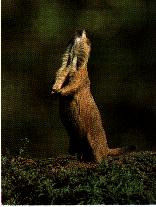

Another

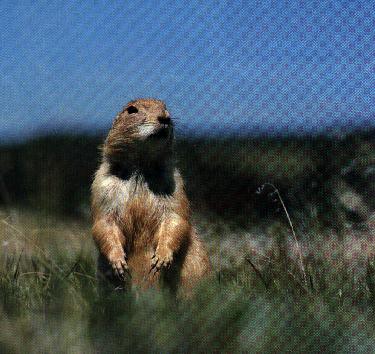

call given by prairie dogs has also attracted the naturalists' attention. From

time to time a prairie dog will stand on its hind legs, stretch the body as

vertical as possible and throw its front feet high into the air. While doing

all this it begins a very loud call, described variously as a yelp, cry, song

and a yip. While it is amusing to watch one prairie dog do this, jump-yipping

soon spreads through the colony creating a contagious and wild dance. Naturalists

believe that jump-yips probably help family groups maintain their territories,

and may possibly be an "all-clear" signal once a predator has left

the vicinity.

Another

call given by prairie dogs has also attracted the naturalists' attention. From

time to time a prairie dog will stand on its hind legs, stretch the body as

vertical as possible and throw its front feet high into the air. While doing

all this it begins a very loud call, described variously as a yelp, cry, song

and a yip. While it is amusing to watch one prairie dog do this, jump-yipping

soon spreads through the colony creating a contagious and wild dance. Naturalists

believe that jump-yips probably help family groups maintain their territories,

and may possibly be an "all-clear" signal once a predator has left

the vicinity.

A certain prairie dog behavior has been described as kin recognition, family member identification or brood discrimination. But what they are doing is kissing. Black-tailed prairie dogs kiss when they meet within a family's territory. It typically goes something like this: a prairie dog, uncertain about the identity of a neighbor in her territory, cautiously creeps toward the other. She opens her mouth showing her teeth. If the other prairie dog is a family member, they will touch their mouths for an instant or for several seconds. Once they have kissed, prairie dogs may groom each other, nibble at one another's fur or wrestle around in mock battle. As with jump-yipping when two prairie dogs kiss a chain reaction often follows with a colony full of kissing prairie dogs.

While the social life of prairie dogs is interesting and much studied, their role in grassland ecology is equally fascinating. Historically, bison grazed patches of mixed grass prairie short enough for prairie dogs to colonize. As prairie dogs fed upon and trimmed the vegetation, it shifted from a mature prairie to a more disturbed state with more weedy broadleaf plants. Under initial pressure of prairie dog grazing, the grass grew more rapidly and was richer in nutrients. Increased abundance of the weedy broadleaf plants attracted pronghorn antelope. Bison, mule deer and elk also visited prairie dog colonies to feed upon the nutrient rich grasses. Although elk and bison are gone from most of the grasslands of the Great Plains, prairie dog colonies continue to support the biodiversity of the great plains by attracting a variety of animal species. These include fairly common and widespread species such as meadowlarks, horned larks, cottontail rabbits, and deermice as well as species with closer ties to the prairie dog colonies such as burrowing owls. Burrowing owls feed upon insects and small mammals around prairie dog towns and depend upon prairie dog or badger holes for their nests. Many other uncommon or rare species of grassland animals in the Boulder Valley frequent prairie dog colonies. These include golden and bald eagles, ferruginous hawks, badgers, prairie falcons. Black-footed ferrets, an endangered species now extirpated from most of their range depend almost entirely upon prairie dogs for food and shelter.

Not

only do they have far reaching impacts like people do, but they live in family

groups, and have an elaborate system of communication (well the yipjump is not

quite the Internet, but it meets the prairie dogs' needs). They kiss, wrestle,

and defend the boundaries of their territories. When the landscape does not

suit them, they change it to be safer and more comfortable in their homes. The

prairie dog modified landscape attracts a distinct group of animals just as

our cities and towns attract pigeons, racoons, house sparrows and fox squirrels.

Not

only do they have far reaching impacts like people do, but they live in family

groups, and have an elaborate system of communication (well the yipjump is not

quite the Internet, but it meets the prairie dogs' needs). They kiss, wrestle,

and defend the boundaries of their territories. When the landscape does not

suit them, they change it to be safer and more comfortable in their homes. The

prairie dog modified landscape attracts a distinct group of animals just as

our cities and towns attract pigeons, racoons, house sparrows and fox squirrels.

However, unlike human populations which continue to grow and spread out over the landscape, the extent and numbers of prairie dogs are shrinking. Out of an estimated 100 million acres of active black-tailed prairie dog colonies, about 2 percent remains. While poisoning programs aimed at preserving agricultural productivity have been responsible for most of this decline, urban development and bubonic plague are becoming significant concerns in the last few decades. The black-footed ferret has been driven to verge of extinction by the reduction of prairie dog colonies. Burrowing owls have been extirpated from the Boulder Valley. Conservation biologists are concerned that other species dependent upon prairie dogs may follow in what has been described as an "ecological train wreck."

The Open Space Department has begun work on a grassland management plan in an attempt to head off such a train wreck in the Boulder Valley. The Department has worked over the past three years with a committee of farmers, rural residents, environmentalists, animal rights advocates, land managers and interested citizens to develop a set of goals for prairie dog management on Open Space. The initial phase of the plan concentrates on prairie dog management and seeks to reduce the conflicts between prairie dogs and adjacent land uses by establishing a system of prairie dog habitat conservation areas throughout the Open Space land system.

In

order to develop the preserve system, the Open Space land system has been broken

down into several categories. The first category is "ecological suitability."

Most grasslands on Open Space were considered to be ecologically suitable for

prairie dogs. Coniferous forests, wetlands, tallgrass prairie, and riparian

areas are ecologically unsuitable.

In

order to develop the preserve system, the Open Space land system has been broken

down into several categories. The first category is "ecological suitability."

Most grasslands on Open Space were considered to be ecologically suitable for

prairie dogs. Coniferous forests, wetlands, tallgrass prairie, and riparian

areas are ecologically unsuitable.

Ecologically suitable lands were then considered for their "cultural suitability." Irrigated crops and pasture were considered to be culturally unsuitable because the Open Space Department has a part of its mission, the preservation of agricultural land uses in the Boulder Valley. Areas being reclaimed from a previous land use (for example, the gravel mine along Coal Creek or the strip farming on Gunbarrel Hill) were also considered culturally unsuitable-at least until a healthy native grassland is restored. As part of the cultural suitability analysis, the Open Space Department also wanted to insure that there would be prairie dog colonies in places where people could enjoy observing them and where educational activities could be focused.

The remaining suitable habitat was then examined more closely, using generally accepted principles of preserve design. For example, large, contiguous blocks of habitat usually make better preserves than small, isolated blocks. The preserve design was then modified for the specific requirements of prairie dogs such as soil type, slope, vulnerability to plague and barriers to dispersal. The requirements of those species which depend upon prairie dog colonies (burrowing owls, raptors and badgers) were also taken into consideration when developing the preserve design.

The resulting preserve system includes approximately 4,600 acres in seven habitat conservation areas. Prairie dogs will exist essentially undisturbed in habitat conservation areas where management activities will focus upon encouraging prairie dogs to create and maintain habitats for a variety of plant and animal species. The first phase of the grassland management plan also contains a set of policies describing in greater detail the Open Space Department's control and monitoring programs, educational initiatives, and public process as it relates to prairie dog management.